If you haven’t read part 1 of this series yet, here it is. You’ll need to read it to understand what we’re talking about here.

How can we (safely) achieve the same effect as our three singers?

We need to figure out what our ear is hearing. It sounds like talking or calling out, way higher in the range than one would usually expect - so how are they doing this without causing vocal damage? I believe the answer lies in acoustics as a way of boosting the sound efficiently.

(If you don't want to understand the acoustics behind belting, you can skip ahead to the disclaimer and exercises at the end).

To understand how this can help, let’s look at some simple notions of acoustics, as applied to the singing voice. Basically, an acoustic signal, such as the signal produced by a piano string or by our vocal folds, is composed of a pitch (the note we hear) and lots of other frequencies all vibrating at the same time. We call these extra frequencies ‘harmonics’ or ‘overtones’ and they play an important role in shaping the sound our ears here. When a complex acoustic signal such as this passes through a resonator, some of the overtones get amplified and others get weakened. It is largely the shape and size of the resonator that determine which parts of the signal get amplified and which don’t - each resonator has a unique ‘recipe’ for which parts of the signal it boosts. Different recipes are interpreted by our ears as different timbres - this is what makes our ears able to hear the difference between a piano and a violin, even if they play the same note.

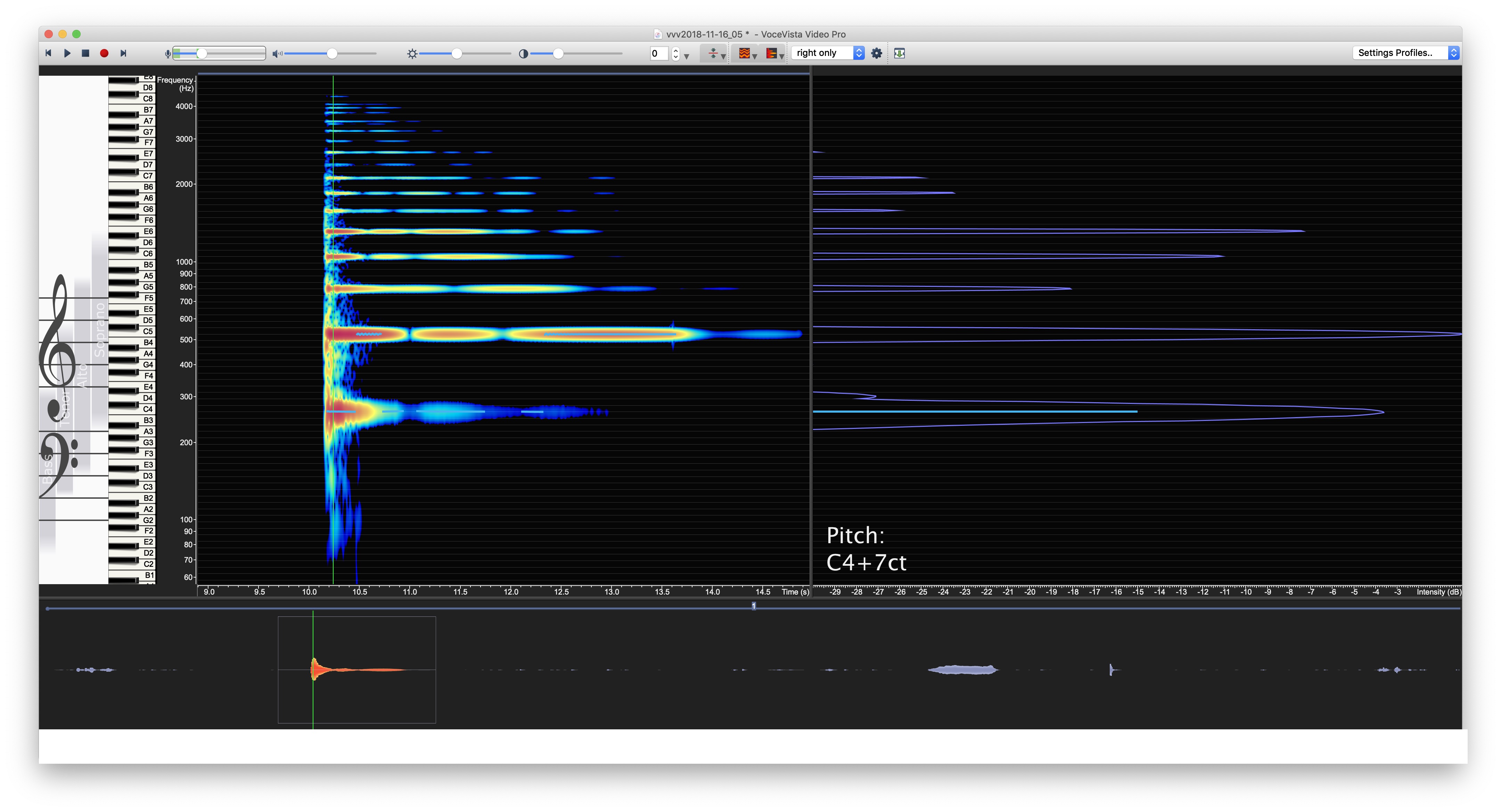

Here’s an acoustic analysis of the note middle C, played on a piano

The horizontal lines you see represent the harmonic overtones, the lowest line is the note being produced, the others all the extra harmonic frequencies vibrating at the same time. If you look at the right hand part of the screen, you can see that some of the lines are longer than others - the longer the line, the more amplified that particular frequency is. In the piano signal, we can see the second harmonic (second line up from the bottom) is strongest, followed by the first (the actual note), then the fifth etc. (I’m aware that we should really say ‘fundamental frequency’ rather than ‘first harmonic’ - but we’re simplifying for the purposes of this article). The strength of the harmonics, which ones are amplified and which are not, is what our ear interprets as timbre. Logically, if we were to look at the same note played on, say, a violin - we’d see a different harmonic recipe. Let’s do that:

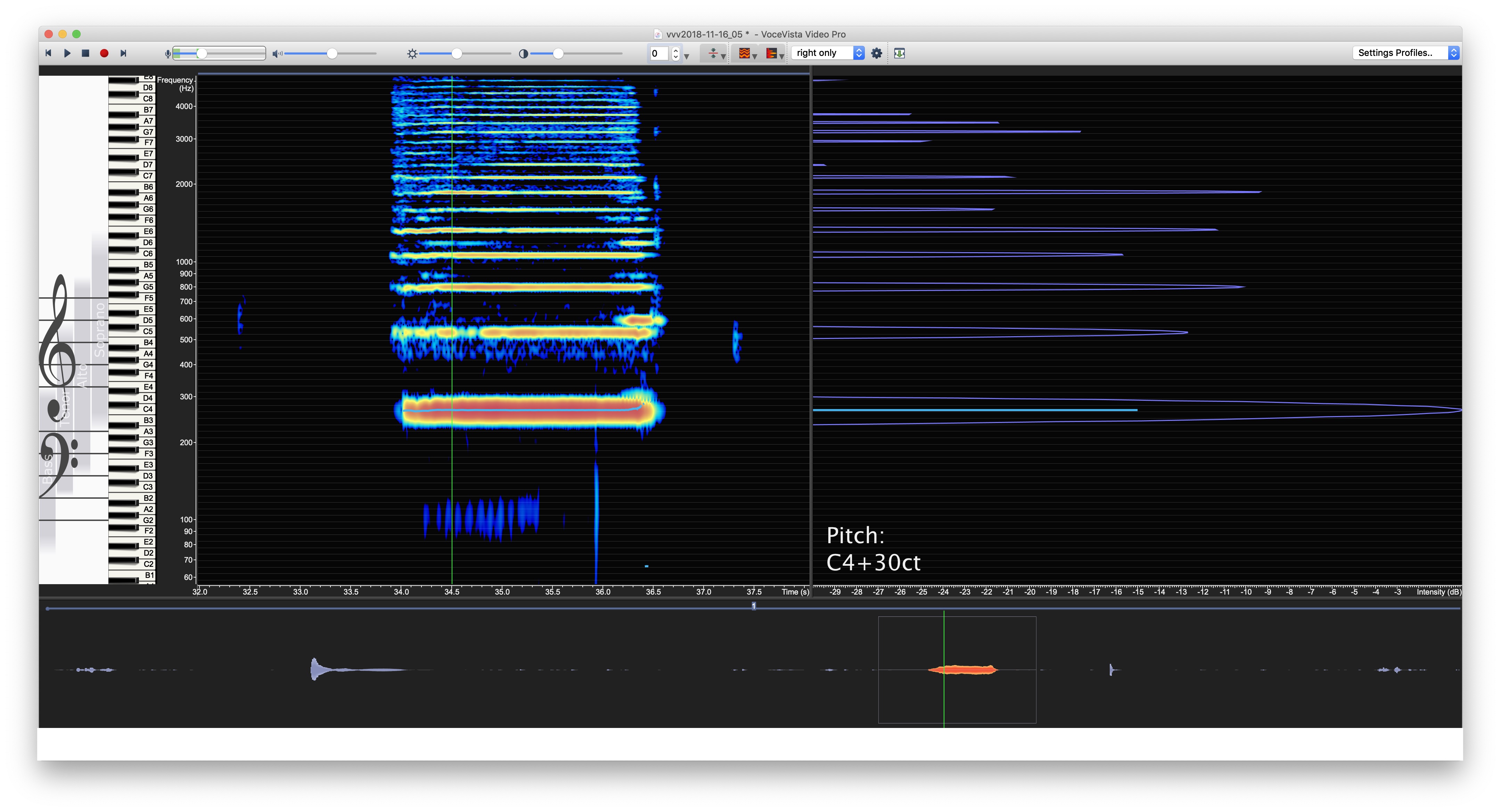

If you look at the right screen here, you’ll see very clearly that different harmonics are amplified. The first line is the strongest, followed by the seventh, then the third etc. This different picture represents a different timbre and shows in image form how our ears are able to hear ‘oh that’s a violin’ or ‘oh that’s a piano’. This happens because the piano's resonator and the violin's are not the same shape or size. We might call differences in harmonic recipes In the human voice ‘chest’, ‘head’, ‘mix’ or - in the case of this article - ‘belting’

What we can take away from this is that harmonic recipes are what our ear interprets as timbre, so if we want to reproduce a given timbre, it’s helpful to know what its harmonic recipe is.

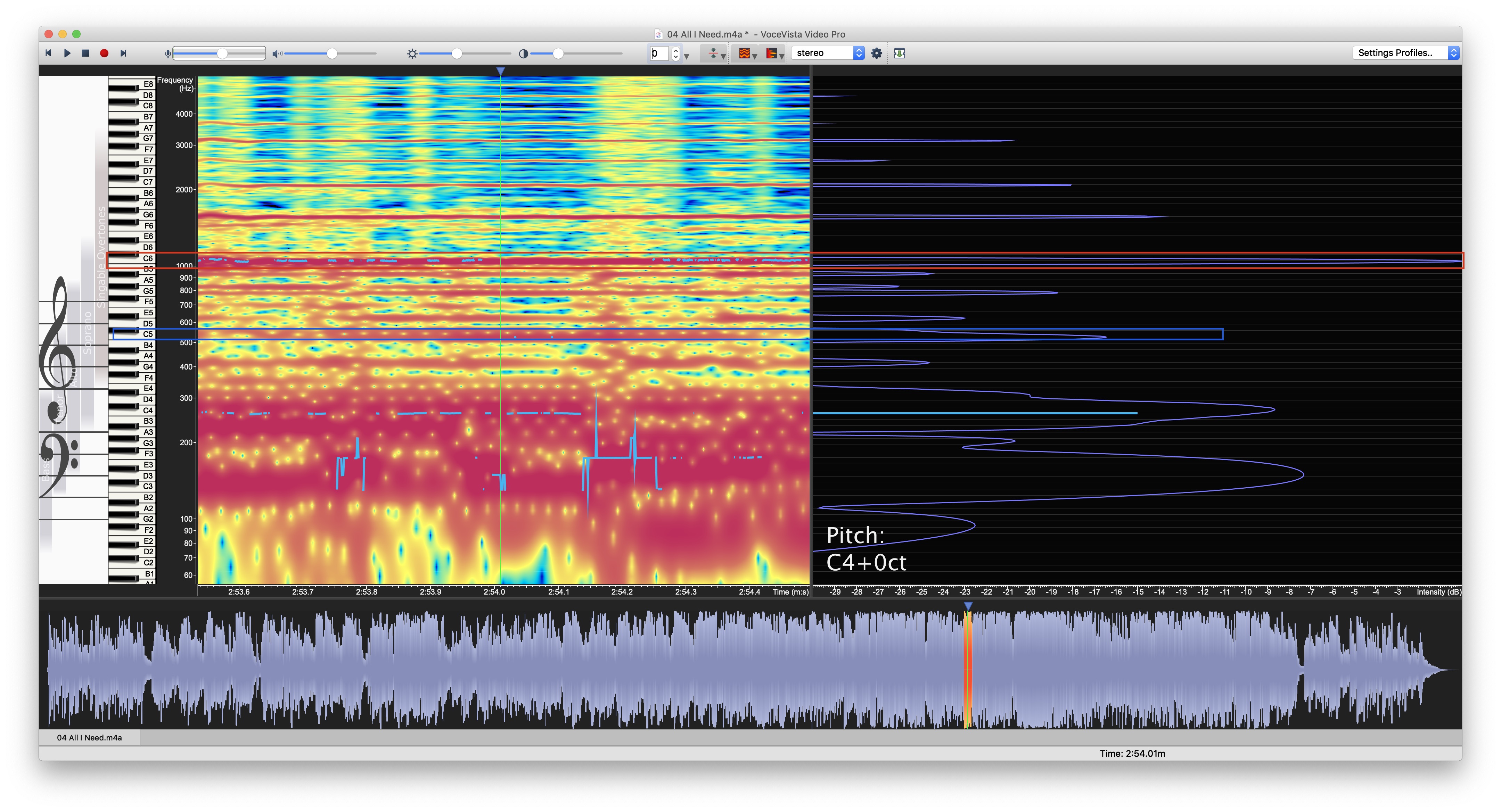

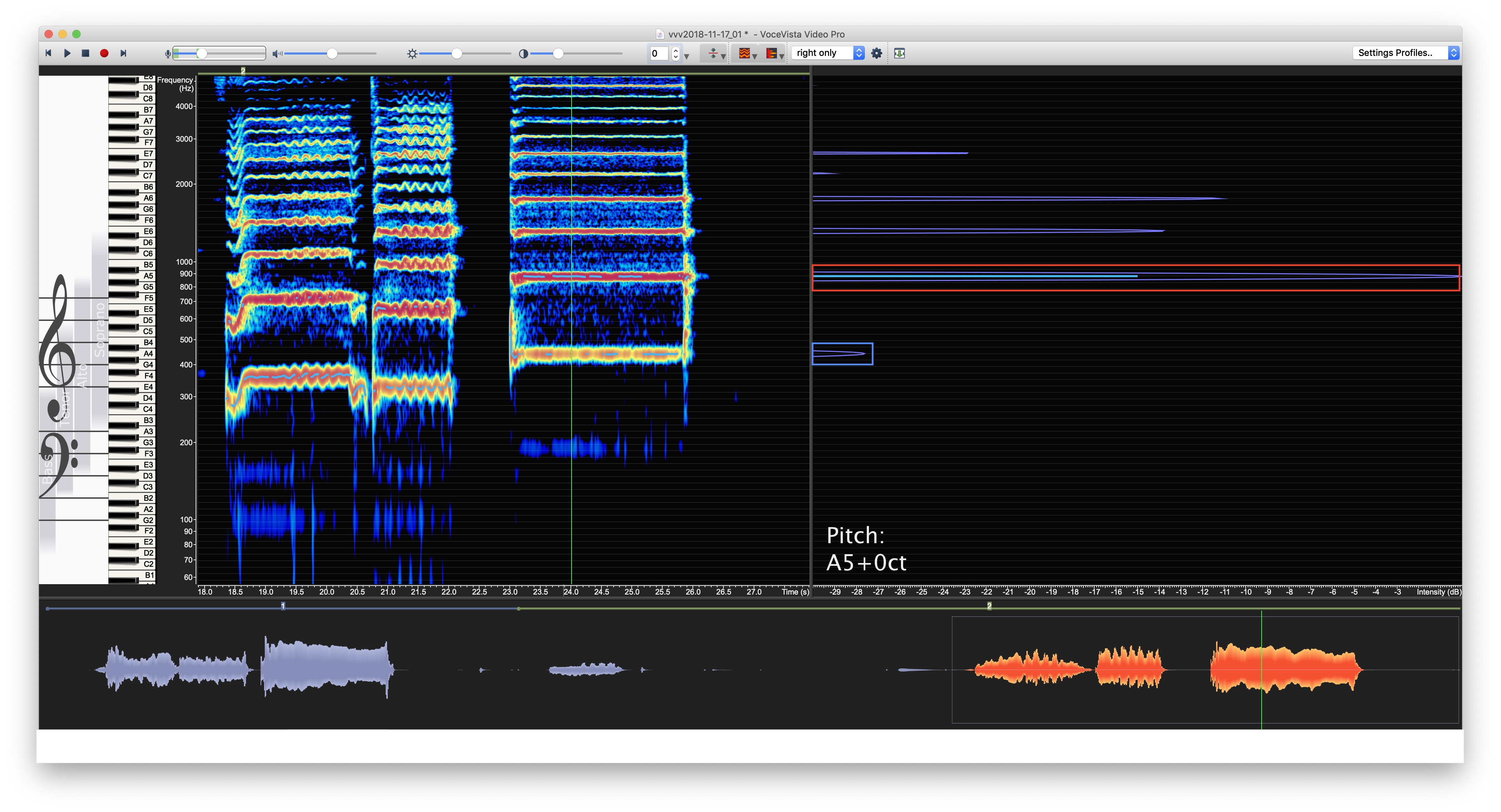

In order to find out what the harmonic recipe of our singers is, we simply have to run their voices through the same programme. Here’s Caissie Levy:

Because the programme is dealing with her voice and the accompaniment at the same time, I’ve marked the first and second harmonics of her voice in blue and red respectively to make it easier to read - you can ignore the rest. We can clearly see that the second harmonic (marked in red) is very strong compared to the rest.

Let’s see if Laura Osnes is doing something similar:

Once again, I’ve marked the first two harmonics to make it easier to read and we can see that the second harmonic is, again, incredibly strong.

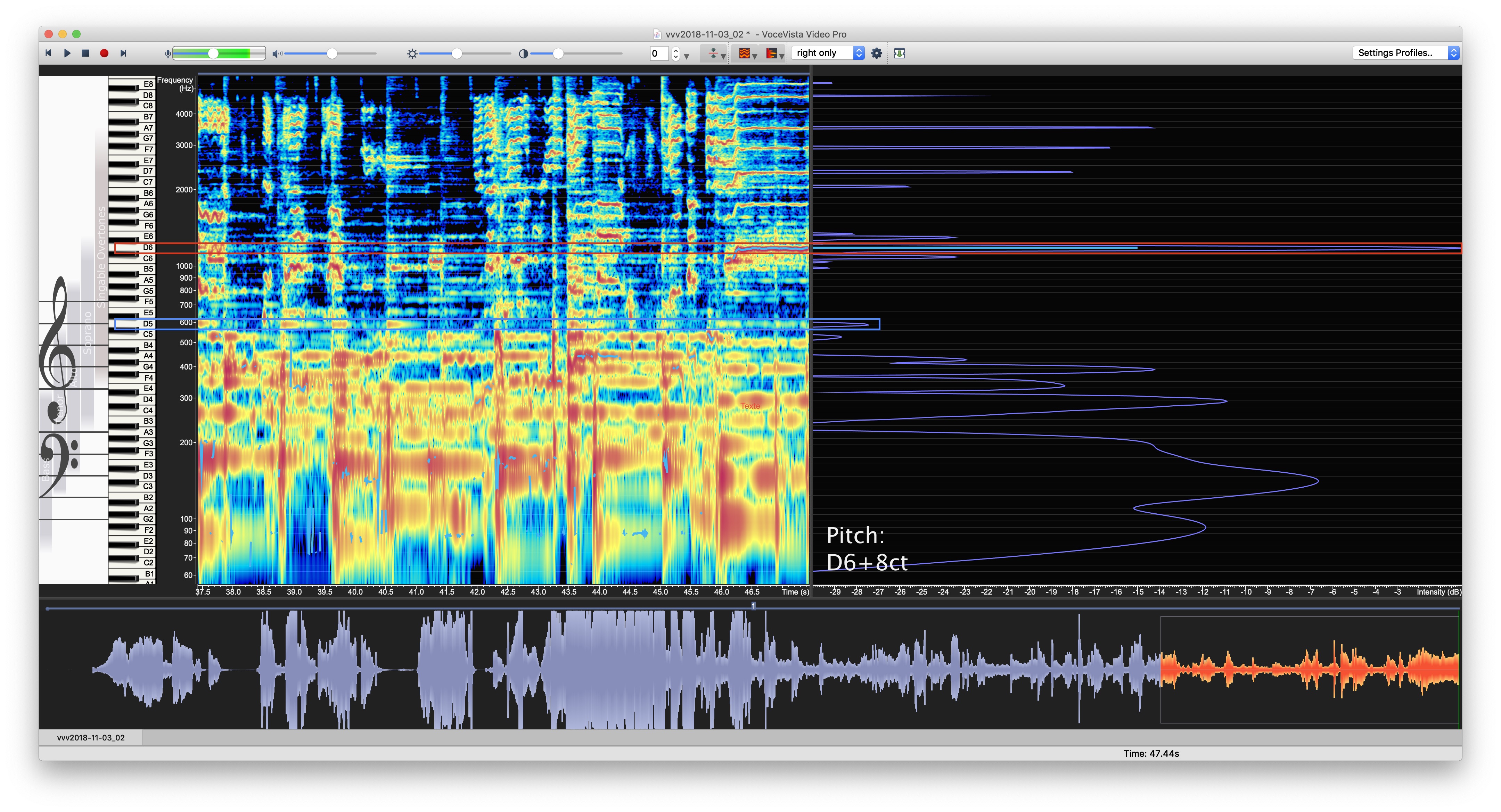

I couldn’t get a good read from Jeremy Jordan (there was too much background noise on the recording) so I sang the last phrase of the song myself and belted the end - obviously that’s no guarantee that Jeremy Jordan is doing the same thing, but the whole point of including him was to show that men can and do belt, so even though this image is not of Jeremy’s voice, it is of a professional male singer belting the same song, so I feel it's sufficient to make the point.

Because I was singing without accompaniment, we get a lovely clear reading of only the harmonics of my voice and we can see, very easily, that the second one is considerably stronger than the others.

So, if we can learn to amplify the second harmonic in the upper range, we should be able to create the characteristic timbre of belting. This makes good acoustic sense because certain acoustic set-ups can make things easier on the larynx, a bit like a cushion effect. Explaining the complex interactions of the vocal tract and the vocal folds is beyond the scope of this article so, suffice it to say that reinforcing the second harmonic helps create a belt-like timbre AND makes things a bit easier on the vocal folds whilst they’re doing something super complex. What’s not to love? (If you do want to understand more about acoustics and vocal function, a good basic primer is Principles of Voice Production by Ingo Titze)

How can we do that?

We need to come back to the notion of resonators. We only have one resonator in our voice (the vocal tract) - our chest doesn’t resonate, nor does our head and neither do our sinuses (at least not in any way that actually affects the sound - plus all of those places are full of gooey stuff that would make them pretty terrible resonators anyway). Does that mean that, like the piano or the violin, we are stuck with one harmonic recipe? No! The human vocal tract is superbly unique in that it can change shape at will. All we need to do is find the shape that makes the second harmonic stronger and we’re on.

The answer to this lies in our choice of vowels. Each vowel is basically a different shape in your vocal tract, so find the vowels that like to reinforce that second harmonic range on the higher pitches, and you make belting a whole lot easier. We can further simplify it if I tell you that open vowels, open mouth shape and a shorter vocal tract are the three things that will help. In fact if you look at the singers in our examples, or indeed at any singer who belts - you’ll most likely notice a wide mouth opening and modification of the vowels to make them as open as possible (think of Elphaba singing ‘bring may down’ rather than ‘bring me down’ at the end of defying gravity). If the singers in question have very visible larynges, you will almost certainly see them rise (thereby shortening the vocal tract) during this process too.

Disclaimer

Before we look at tips on how to try out belting in your own voice, please remember that good belting does not feel uncomfortable, painful or strained. It is energetic, but feels easy in the throat at all times. Also remember no one other than you is responsible for your vocal health, so if something feels painful when you’re doing it, it’s wrong and you should stop. I accept no responsibility for incorrect application of the information in this article - listen to your bodies and, if you’re struggling to do this on your own, seek out a specialist teacher of belting. Do not attempt these exercises if you have a vocal pathology, are suffering from vocal fatigue or have a breathy sound in your voice - belting and breathy tones do not mix well.

Get practising!

The following tips will help you work on belting

- Train yourself to take your talking voice above the break area. Belting is not a head voice based sound. You can do this by simply saying ‘hey there!’ (notice 'saying' rather than 'singing') on gradually higher pitches, as if you were talking over a loud crowd of people. Start around C4 in your talking voice and go up in semitones, gradually letting it become a gentle call. Don't go above C5 for now.

- As you go higher, you will need to strongly reduce your feeling of airflow. If you’re used to singing ‘on the breath’, you may even feel like you’re singing whilst holding your breath totally. This is quite normal when belting.

- Choose a word with an open vowel, such as ‘yeah’ to train on. Begin around D4 and say ‘yeah’ in a happy, speaky voice. Feel how little air this uses. As you move up semitone by semitone, let your larynx raise up a little and begin to increase the volume gently so the voice becomes more of a call out - really hold back the air (it may feel like you’re calling out backwards, or inwards). Train this up to around a C5 for now.

- Pick a song with a note above F4 that you’d like to belt and replace that word with a ‘yeah’ for now. Do it until the called-out ‘yeah’ feels easy, then try it with the real word (you'll very likely need to open the vowel up and change it a little - always let the feeling of the called out 'yeah' take precedence over the purity of the vowel of the original word - even if it feels like you're butchering it).

Come back next week for a video workout to help you get the hang of it even more. Until then, train yourself using these tips and, above all, have fun with it!