It feels like a buzzword in the vocal technique word over the last few decades - people talk about adding twang to a voice, or using oral twang, or nasal twang - some people talk about thick or thin twang, others still talk about operatic twang or twang for belting. It seems like it’s the magic thing to fix everyone’s voice! (Spoiler alert: it’s not - it’s useful, but not the holy grail of vocal technique. There is no holy grail!)

You might already know what twang is (in which case, why are you reading this? Go and have a sit down and a twix!), but many people don’t. In fact it’s one of the most frequent questions I get from people via e-mail on the courses I run.

What is it?

Despite what teachers of certain approaches would have you believe, twang is not a recent invention, nor does it ‘belong’ to anyone. The name is fairly recent, perhaps. But the thing it describes isn’t - we’ve been talking about it for centuries.

When people say twang, what they mean - usually - is a strong amplification of the harmonic energy around 2.5 - 5 kHz. That’s it. Lots of energy in the higher harmonics of the voice. It has been called squillo, the singer’s formant, ring, ping, vocal edge, brassiness and many other names. The term ‘twang’ was first suggested as a way to describe increased energy in this zone in the 1960s by William Vennard1.

So it’s definitely not a recent thing and no one can claim ownership of it. Doesn’t stop people from trying, mind you - you just have to go onto various singing technique forums to see teacher’s fighting over who owns what. Whilst it’s tedious to be part of, it’s quite fun to watch - especially if you have popcorn...

So, all ‘twang’ really means is ‘added brilliance in the resonance’. Now why would that be useful - that’s a more interesting question.

Do I need it?

The answer to that is ‘it depends on what you’re planning on doing’. If you’re a classical singer (especially if you’re a man), then it’s a key part of how you get your voice to carry over the orchestra. Increasing harmonic energy in that particular range enables the singer’s voice to inhabit a part of the sound spectrum where the orchestra produces very few harmonics - so their voice can sneak past the orchestra and we can hear them (it would be folly to imagine that a human voice can outsing a symphonic orchestra from a volume point of view - tell that to those snobs who would have you believe that singing without a microphone somehow makes you a better singer... it doesn’t. It’s just different - but that’s for another article!)

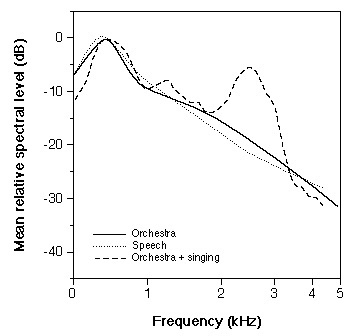

Take a look at the image below, from NCVS (you can read their explanation of it here http://www.ncvs.org/ncvs/tutorials/voiceprod/tutorial/singer.html) - you can clearly see that the orchestra alone does not produce many harmonics in the 2.5 - 5kHz range, but when the singer’s voice is present, there is a peak of energy in this area.

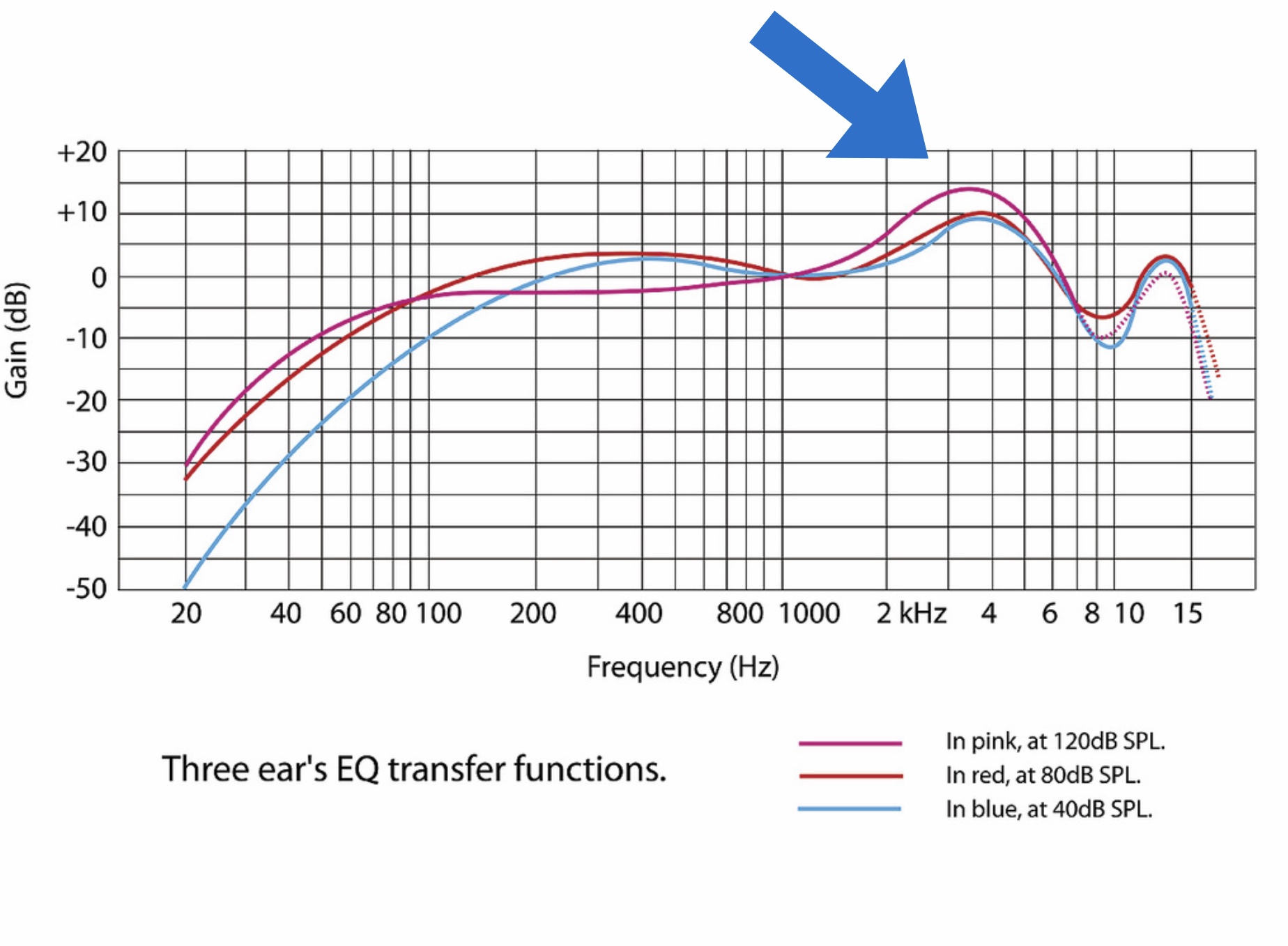

It’s interesting as a projection tool because this is also the frequency range where the human ear is most sensitive2. Effectively, classical singers are cleverly adding harmonic energy to their voices in exactly the right range of frequencies so that you can hear them in spite of the orchestra. Look at the image below, showing clearly that - independently of actual volume in dB, the ear hears frequencies in this range as being louder than others

(Source : https://www.soundonsound.com/sound-advice/how-ear-works )

You’ll also hear this sound in a lot of Gospel music - it gives the characteristic brassiness to the sound (many Gospel singers call it a Gospel squall! How fabulous is that?!) and more recently, it has appeared in certain styles of pop - think Lady Gaga, Demi Lovato, Hozier etc. It adds clarity, brightness and strength to the voice.

Pop singers have a lot more freedom in their use of it than do classical singers, of course, because pop singers use amplification and therefore can use different quantities (and qualities) of ‘twang’ to create different effects as they aren’t dependent upon it to be heard - it becomes a kind of artistic effect for them rather than a basic ingredient of their sound.

How is it produced?

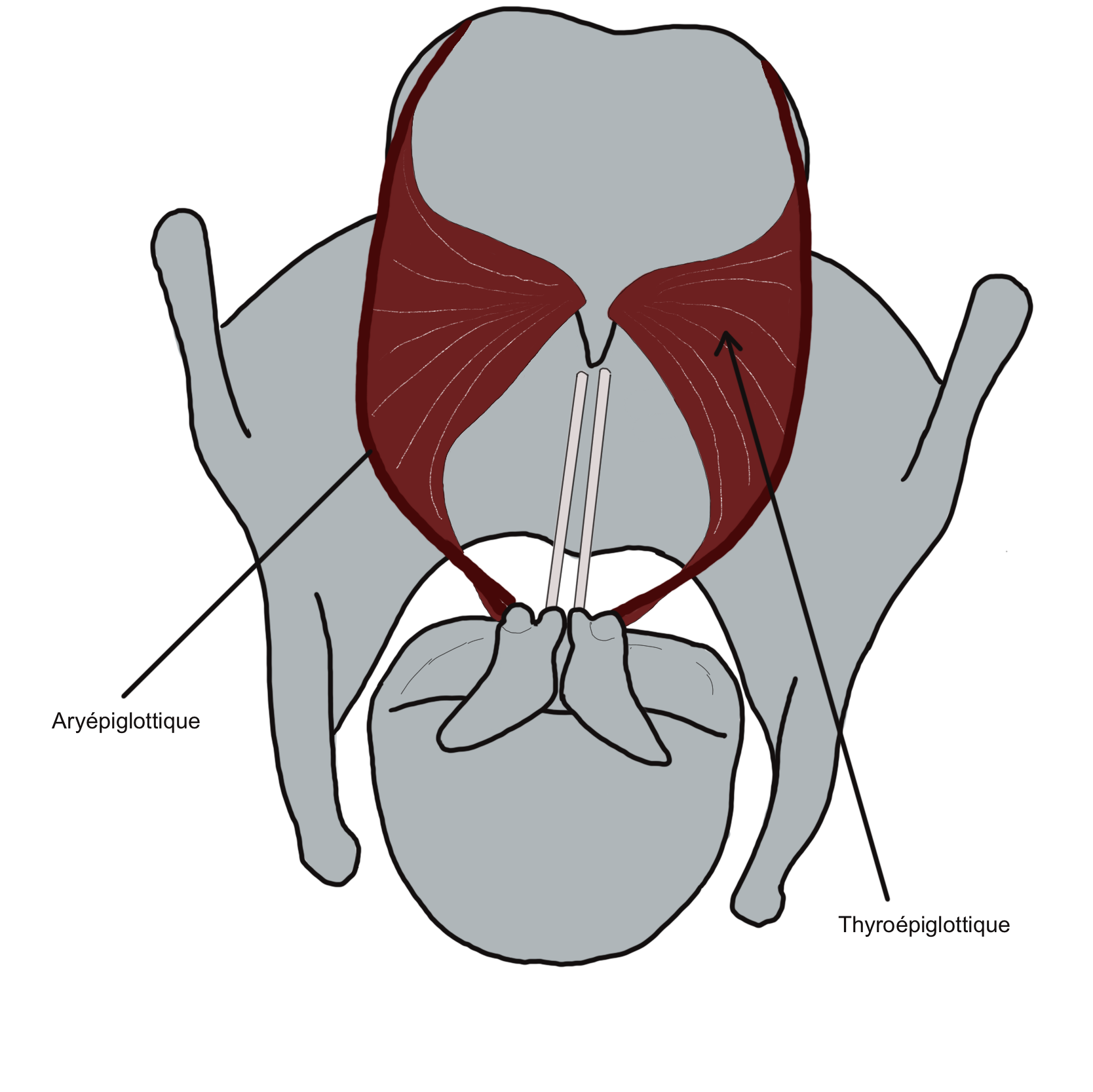

The most common explanation of twang is that you tighten the aryepiglottic sphincter (who knew you even had one?!) - the aryepiglottic sphincter is just a fancy name for the muscles that help close up the inlet to the larynx (the thyroepiglottic muscle and the aryepiglottic muscle - see image below). You could just call it the twanger if you want to make your life easier - but you get to sound really fancy if you say ‘aryepiglottic sphincter’ - also, it’s quite fun to say ‘tighten’ and ‘sphincter’ in the same sentence in polite company…

By tightening this space, we effectively create a mini resonance chamber within the larger resonance chamber of the throat and this peculiar shape allows for the change in timbre associated with twang. Imagine the top of larynx closing up like a drawstring purse, whilst the throat around it remains fairly wide.

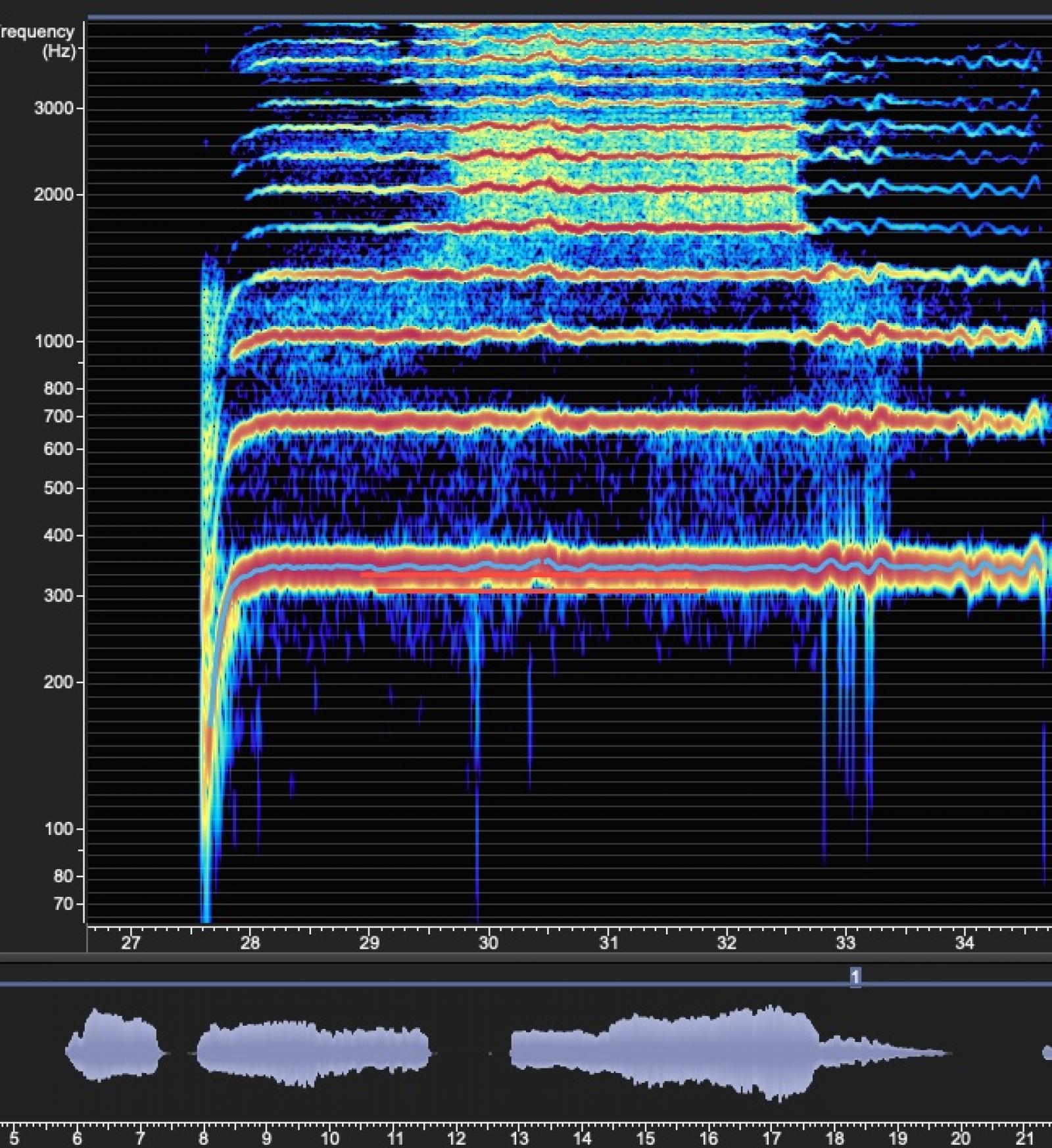

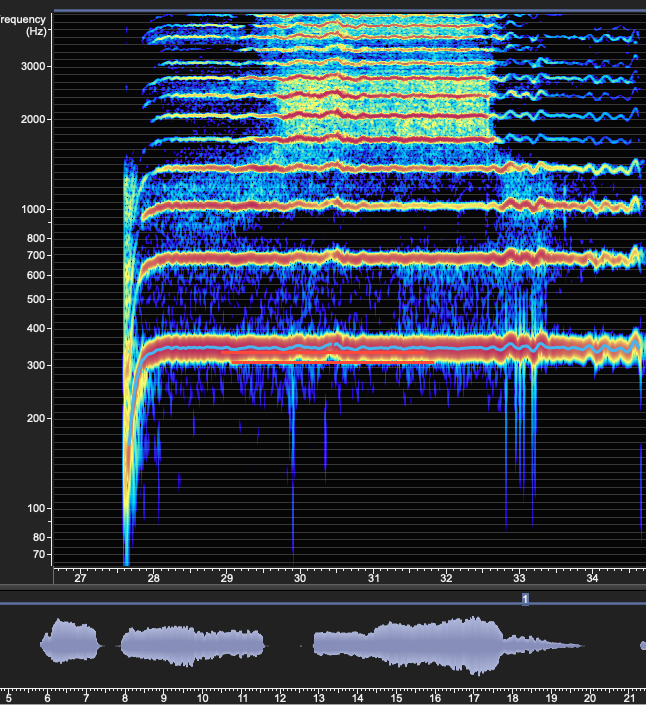

Look at this picture of the same vowel without twang, then with twang added, then without twang again - if you look at the area above 2kHz (frequencies are shown on the left of the image), you can clearly see the harmonics strengthen in the middle version - this is the added brilliance or projection that comes from twang.

It’s not the only way to do it, mind - from an acoustics point of view, you could theoretically achieve the same thing with anything that allows you to boost energy in this area (vowel tuning could help, changing laryngeal position could help etc...)

Get yo twang on !

Try imitating the following sounds to find what twang feels and sounds like in your own voice. Don’t panic - it will likely sound ugly, sharp and piercing. Once you’ve found it, play around with adding different quantities of twang in order to help your voice carry.

- Cat Meeowing

- Duck quacking

- Baby wailing

- Steretypical American accent

- Witch Cackling

So, if you need a bit more carrying power or cutting edge in your sound, give a bit of twang a whirl - you never know, you might just enjoy it!

References

1. https://doi.org/10.1159/000262995

2. Gelfand, Stanley (2011). Essentials of Audiology. Thieme. p. 87. ISBN 1604061553. “hearing is most sensitive (i.e., the least amount of intensity is needed to reach threshold) in the 2000 to 5000 Hz range”